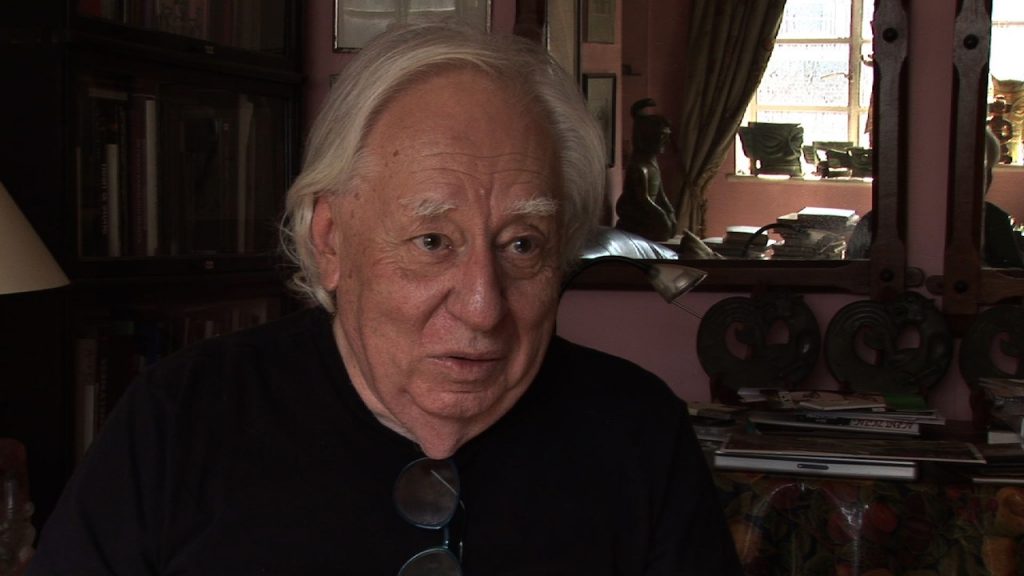

It’s not often nowadays that a really major artist slips through the net. In Dave Pearson’s case the fact is the more surprising since his major enterprises, launched usually in municipal galleries in the North of England, were invariably both extremely ambitious and not at all difficult for ordinary spectators to construe and empathize with. His enormous body of work, product of an equally colossal creative energy, was rescued from oblivion after his death by a small band of devoted colleagues, who formed the Dave Pearson Trust to preserve it. This Trust is the sponsor of the present exhibition, which is the first big showing of Dave Pearson’s lifework in London. It is fitting that it should be held in a gallery with two floors of artists’ studios directly above the exhibition space, since the life of the studio, and life in the studio, were the essence of Pearson’s existence.

The exhibition is divided into sequences that offer a concise overview of who David Pearson was and what he did. The first section consists entirely of self-portraits. Like Rembrandt and Van Gogh before him, Pearson continually interrogated his own physical appearance, and through it his own character. Though the influence of Van Gogh in particular is apparent in a number of these works, what is particularly striking about them are the constant shifts of both mood and style. Every time Pearson asked the fundamental question – ‘Who am I?’ – he came up with a different answer. Yet these multiform answers cohere, when one sees them together, into a complex whole. What one has here is the multiform nature of contemporary existence, yet, at the same time an acknowledgement that, in Pearson’s case at least, all these different appearances had their roots in a single core – one of driven, obsessive creativity.

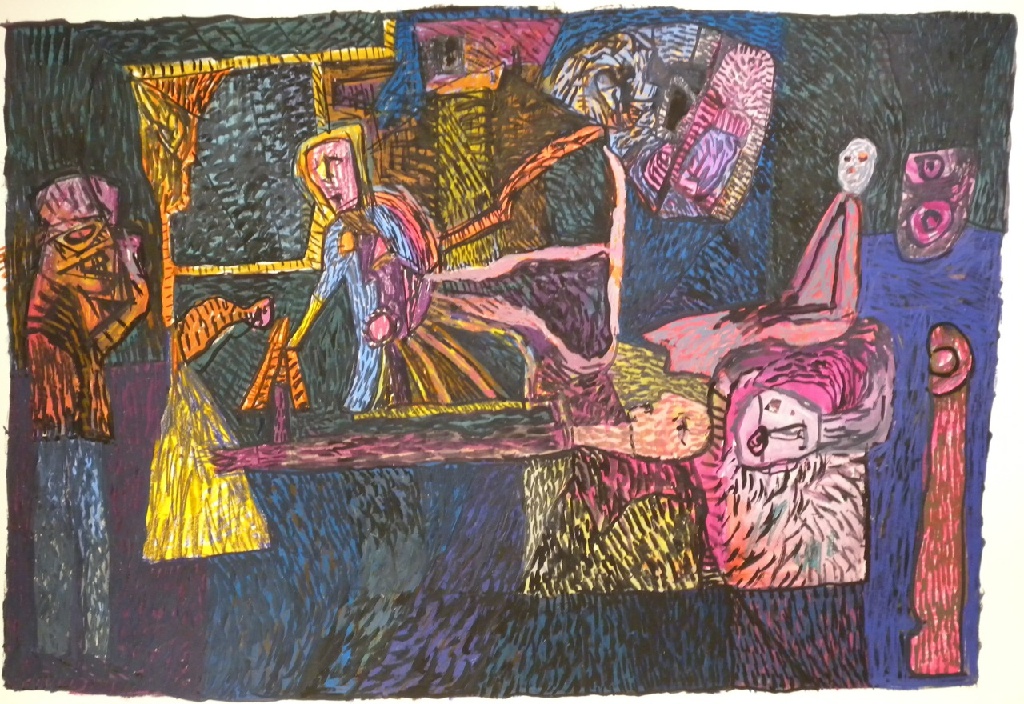

The next and largest section of the show consists of selections from two huge sequences, Sailing to Byzantium and Byzantium. The inspiration is not directly from the history of the Byzantine Empire itself, but comes from the famous poem, Sailing to Byzantium, written by W.B. Yeats. This is a text, universally acknowledged as one of the greatest poetic utterances of the 20th century, over which literary critics argue endlessly. Some see it at optimistic, some as deeply pessimistic. It also reads both as a celebration of artifice and as a rejection of it. One may perhaps get a glimpse of why Pearson was fascinated with this particular text from what Yeats himself had to say about the city of Byzantium in his prose explanation A Vision:

I think that in early Byzantium, maybe never before or since in recorded history, religious, aesthetic and practical life were one, that architect and artificers – though not, it may be, poets, for language had been the instrument of controversy and must have grown abstract – spoke to the multitude and the few alike.

That is, these sequences of paintings are not esoteric works addressed to the few, but directly popular. In their full form, the Byzantium sequences full embrace the spectator. He or she does not merely witness them, but becomes part of them. These paintings, crowded with figures and incidents, are an attempt at a fully immersive art.

The corridor leading from this main space contains smaller paintings, intended to show when Pearson produced when working on a more-or-less domestic scale. To the left of this corridor is an enclosed space where Derek Smith’s excellent biographical film can be seen in its entirety. This room also contains a few examples of the small ‘models’ Pearson made to amuse young people and to give away as presents. These a little tableaux, made using toy animals bought in local markets as part of their raw material. They are charming demonstrations that Pearson’s art also had a playful, light-hearted aspect.

The show is an autobiography – one of the greatest composed by any 20th century British artist. At the end of the corridor there are two further spaces. The first of these has been used to display a handful of major canvases, not part of any sequence, that give a glimpse of Pearson’s artistic relationship to various aspects of European High Modernism of the first half of the 20th century, in particular to aspects of Surrealism, and also to one facet of Russian Futurism. The artists who come to mind when one sees these large sonorous works are always those who avoided the clichés of the particular art movements with which they are now associated. In the case of Surrealism, the comparison is one with André Masson (1896-1987). In the case of Russian Futurism, there is an even closer link to the art of Pavel Filonov (1883-1941).

This space also offers a Powerpoint presentation of Pearson’s extraordinarily rich series of illustrations to the Book of Revelation. These illustrations tie him to a very special part of the British Romantic tradition – to the work of William Blake.

The final room of the exhibition is devoted to work inspired by Pearson’s final illness and death. He was diagnosed with cancer in 2003 and died in 2008. In this series of images, too, one finds the echo of a celebrated poem, Dylan Thomas’s villanelle Do Not Go Gentle Into that Good Night. The images are, on the one hand, very direct, with a use of photographic material that brings the sordid reality of mortal illness very close to the viewer. Other works, however, manage to convey the artist’s situation in a different way – they seem at first sight to be unspecific, complex abstract constructions, but, examined more closely, become brutally, terrifyingly truthful.

The show is an autobiography – one of the greatest composed by any 20th century British artist. It is also, I think, a shining example of ‘what only paint can do,’ even though not all of it is painting. Tellingly, this phrase was once used by Ernst Gombrich about a depiction of a vase of flowers, now in the Scottish National Gallery in Edinburgh, painted by Jean-Baptise Chardin. It’s hard to think of two artists more unalike than Chardin and Pearson. Or of two who plead the case of painting more eloquently.

Edward Lucie-Smith 2012

Bermondsey Project exhibition